Birds of a Feather

When two brands join efforts in co-branding actions, they set in motion a series of attributes of their personalities that can give rise to a sale avalanche and generate prestige for both

Rodrigo Rocha

For people, cooperating comes naturally. Everyone knows that “nobody is an island” and that “unity is strength”. Well, this is one more resemblance between people and brands. In the integrated and hyperconnected world we live in, those who are able to cooperate prosper better and faster. Therefore, the trend of cross-promotion actions involving co-branding agreements has consolidated in several markets as an efficient way to gain the attention of consumers and generate financial and prestige gains for all involved.

McDonald’s and Ovaltine [Ovomaltine in Brazil], Redbull and GoPro, Amil and Disney – the examples are many and, if we look closely, we can perceive there is something special between the brands, a sensitive harmony that makes partnerships make sense to consumers and have the power to engage and inspire then to buy or change their behavior. The source of this magic is the compatibility between the personalities of the two brands involved.

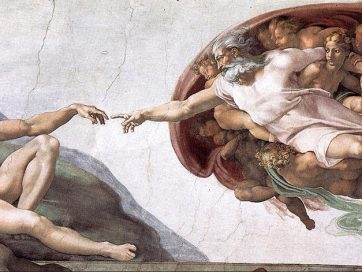

Co-branding actions are like Hollywood couples: people like to see, but they only believe it when they feel that the couple’s chemistry works. Elizabeth Taylor married eight times, but the husband the public recognized as “ideal” was actor Richard Burton. The magic aura that involved the couple ensured the commercial success of the films in which they starred. The equivalent of their success in the 21st century was the “co-branding” of Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt, the “Bradelina” couple. It was interesting how the public reacted well to their union, even as Brad Pitt’s first wife, Jennifer Aniston, to whom the actor was married for much of the 1990s, was a “victim” of their passion. Another indication of the good acceptance of the couple is the worldwide shock with their divorce, which made headlines everywhere.

In the world of brands, Brazil has recently witnessed a similar drama. Since Bob’s, the fast-food chain. was founded, it’s differential was the fact that it was Brazilian and, along with its Brazilianness, was its strategy of celebrating icons of the national culture. One of his most celebrated products was the Ovaltine milkshake, the chocolate powder that was part of the childhood diet of many Brazilians. This affective memory factor was very powerful and immediately triggered people’s goodwill. The fact that Bob’s highlighted the Ovaltine brand in its menu was recognized and celebrated by consumers. So much so that Bob’s is the only fast-food chain where people choose the milkshake before thinking about the hamburger. For both brands it seemed like the perfect marriage. The association was good for both and they were happy for more than three decades.

McDonald’s, meanwhile, seemed to remain aloof. It was a strong, international brand, and seemed pleased with the performance of its milkshakes. It was like Angelina Jolie when she was filming Mr. and Mrs. Smith – she was already on the producers’ A-list and nothing indicated that a partnership might change her already prestigious status. Yet, the partnership with another strong brand, Brad Pitt, made her leap into a whole other level of popularity.

The same happened to McDonald’s, which gained many new consumers when it bought the rights of the Ovaltine brand and added the new milkshake to its menu.

Much like what happens with people, when brands decide to unite, the most important feature for the success the partnership is the perception of compatible personalities. For instance: Red Bull and GoPro. The two brands have in common the fact that they are perceived as brands linked to the world of action sports and adventure, of overcoming limits, of alternative lifestyles. Both were founded by practitioners of extreme sports, businessmen who are far cry from the suit-and-tie style. This similar origin leads both brands to be present in the same real and virtual environments. Both sponsor extreme sports, invest in communication over the internet and show that agility and innovation are their main corporate motivators. That’s why they form a couple that makes sense to the public, who would certainly not be shocked if they invited companies with the same values, such as North Face or Patagonia, for example, for a joint action.

The 4 Es in Co-Branding

As everything else in marketing, the secret of successful co-branding actions is the ability of companies to apply the 4Es during the process of establishing the partnership. Firstly, the project must be Elegant, in the sense that consumers must perceive a positive sense in the association of the brands. They must feel that two big companies are coming together to deliver something that will combine the best of their expertise for the sake of the consumers’ satisfaction. They have to feel that the couple is together because they have things in common, not that the marriage was arranged just to get more money from them. In the case of McDonald’s and Ovaltine, consumers realized that the union would offer them the taste of the chocolate mixture and the capillarity of McDonald’s chain.

Co-branding should also be Efficient. It must bring out the best of each brand and deliver the benefits of both to consumers while generating return on each one’s investment.

Eloquence is a determining factor to validate a co-branding action. The brands must also be equally well-known and meaningful to consumers for their union to have a positive impact on both. If only one brand is widely recognized and the other is not at the same level of recognition, partnership will seem far-fetched and unnatural, and will not deliver the expected positive impact.

If Elegance, Efficiency and Eloquence are present in the partnership, there will be Eminence, or success. In other words, the goals of the brands will be achieved both in terms of financial results and of brand appreciation. In fact, one must take into account that co-branding will always have an impact on brand equity, so each possibility must be carefully evaluated.

I worked directly on the Amil/Walt Disney Co. partnership for a campaign against childhood obesity. Our concern was that, because we were dealing with a company known worldwide such as Disney, the US brand would prevail in the outcome of the partnership. However, after much analysis, we realized that the impact of the Disney brand was related to the entertainment world and not to the healthcare market, where our brand was the strongest of the two. On the other hand, the union of the two would make the campaign more efficient and more eloquent, and showed us that the partnership was, in fact, the best option. The strength of Mickey and his gang would be crucial for the message of pursuing a healthier diet for children to be better heard and absorbed.

The contact with Disney revealed another element in favor of the co-branding effort: there was synergy between their visions. Both companies were concerned about the issue of childhood obesity and this was crucial for the success of the partnership. This initiative led to the Nhac Guide, jointly developed by the two companies and preserving characteristics of the DNA of each one. While Amil brought medical and nutritional expertise, Disney came in with moral strength and the enchantment of its characters. The result reflected the synergy between the companies. It was a clear case of partnership where 1 + 1 added up to much more than 2, because it is much easier to communicate with children through the voices of Mickey, Minnie and Goofy, whom they know and trust, than by other means. Let’s say Amil decided to make the guide on its own, hiring an agency and creating its own characters. Probably the guide would be competent, but its acceptance by the little ones would not be as complete and immediate as it was with the Disney characters, and the results would not be as extensive.

This is one of the key points for co-branding to make sense: companies must have the humility to realize they will only attain the level of excellence they desire if they seek the help of those who have the exact expertise for that activity.

And because the project is relevant to the mission of both companies and matched the values of both, it has been growing and becoming more comprehensive and sophisticated over time. The intention of this project is to create social awareness and is related to the concept of shared value, developed by Michael Porter to describes the social gain that investments made by companies or by associations of companies can generate.

In the specific case of the campaign against childhood obesity, there were potential important benefits for all stakeholders. Healthier children, reassured parents, unburdened healthcare systems, countries strengthened by the prospect of a healthier and stronger future workforce. In other words, in this case, co-branding was able to go beyond the usual goals of increased sales and was able to generate much deeper and lasting results.

Defining the relationship

Because co-branding is a serious thing and has important implications for both parties, one should tread calmly and assess the depth one wants from a relationship with another company. The first step is to evaluate whether the situation calls for co-branding or co-marketing actions.

While co-branding is a marriage and requires that consumers feel comfortable with the union, co-marketing is more like sharing an apartment with a friend, a situation where there is no emotional involvement, but only clear financial advantages for the brands, and which can translate into convenience for the consumer. The idea is that brands complement each other without having their products exactly mingle.

For example, if a company is going to make an video ad saying that a soft drink goes well with popcorn, it might call on a popcorn manufacturer to also invest in the production and dissemination. Co-marketing also opens up the possibility for the companies to use their databases to introduce its partner’s product to its consumers. For example, dealerships chains that feature a particular brand of car stereo. This type of action not only implies considerable time savings by directly accessing the brand’s target audience, but usually also helps build credibility for the partner that is being introduced. All this helps to make the investments more profitable.

In co-branding, the relationship between the brands is deeper and more long-lasting, and often goes beyond “sharing expenses” with marketing. There is an investment of money and talent in the creation of new products that will be evaluated by consumers of both brands. In this case, financial and reputational risk increases significantly. The fashion industry uses a lot of co-branding strategy and offers some very instructive examples. Several large retail chains, such as Riachuelo and C&A, have been regularly partnering with upscale fashion designers.

In these co-branding agreements, the designer creates a special collection for the store chain that will be launched with his or her name on the label, accompanied by the name of the store. The big challenge for fashion designers when developing this special collection is to keep their own style, the truth of their brand, and create garments their clientele and the trade press recognize as consistent with their signature, even as they are proposing clothes and accessories with more affordable prices and a broader size grid than they usually do. For fashion designers, the matter of making larger-sized clothes than they are accustomed to – usually their grid goes up to size 10 (L) at the most – poses a risk in terms of modeling, fitting and fabric utilization. On the other hand, since it is in the DNA of retail chains to be democratic in terms of sizes and to offer products ranging from size 4 to 16 (XS to XXL), co-branding requires fashion designers to be willing to go beyond their usual grid.

For the stores, these actions also imply higher stakes. In addition to investing to advertise the special collections and in the garments themselves (which tends to cost more than those produced for their own brands), retailers are exposed to criticism or praise from customers, bloggers and the trade press. However, despite taking fashion designers and retail chains out of their comfort zone, co-branding is an efficient way to generate brand awareness, expand sales, and win new customers.

In 2014, Riachuelo redefined itself in the marketplace by partnering with the Italian luxury brand Versace. The occasion triggered a huge campaign and the collection was launched at a fashion show during the São Paulo Fashion Week, attended by Donatella Versace herself. At the party ensuing party, the store sold firsthand articles from the collection to attendees. What one saw were fashionists who boasted they’d never set foot in a Riachuelo store avidly buying garment after garment from the collection.

The same frenzy repeated itself almost every month at C&A’s concept store in Shopping Iguatemi, where the chain often holds cocktails to launch special collections by guest designers. At the launching of Alexandre Herchcovitch’s collection, Amir Slama, Adriana Barra and other well-known names created exclusive collections for the chain that were a critical and popular success, accomplishing the mission of widening the horizons of both designers and retailers.

Before the “yes”

Despite numerous success stories of co-branding projects, marketers who may wish to say “yes” to this marriage should first assess a few points.

The first is to evaluate how important it is for you to join another brand in carrying out a specific project. Of course, one is always tempted to try and stay close to market leaders or those with a highly prestigious image. But the question that really matters is whether cooperation will actually make a difference in your project.

Next, one should evaluate whether the project is sufficiently relevant to be worth the risk of associating your brand with someone else’s. You must measure the potential risk involved in the association and its effects among the fans of the brands. When Ovaltine changed partners, it risked of being called an infidel and a mercenary by its public.

Another important care: make sure both brands are at the same leadership tier in their respective niches. Little-known or less prestigious brands tend to disappear in the shadow of their more famous partners. Or, inversely, may be raised to shine in their partner’s sun. For example, mobile phone maker Huawei partnered with German camera maker Leica to produce a smartphone capable of taking better photos.

Another important issue to consider: who will be in charge of the project’s communication? Will it be your company, the other, or both? Whatever the case, who is priority target audience of the actions? Assessing this is important to see if this matches your long-term strategy, and should include the style and content of the messages. Remember: everything reflects in your brand equity.

But if everything is aligned and there is synergy between the companies, then it is time to put hesitation aside and exchange rings.