Expectation and experience are the basis of trust, a fundamental element in connecting reason and emotion, in determining the success of any relationship, and that can strongly impact the results of your company.

Rodrigo Rocha

I have lately been thinking a lot about the concept of trust and the impact that the verb has on our lives. And I noticed that the issue of trust pervades practically every one of our acts – from the simplest and most prosaic to the grandest – and is the fundamental and defining element of the quality of all the personal and professional relationships that we develop.

Precisely because of its ubiquity in every act and relationship, trust is tested every day, in every action and point of contact. Each interaction represents a test. If the result is positive, trust holds or grows; if it is negative, it decreases or disappears. Because of its fluidity and inconstancy, winning trust is among the biggest challenges for companies and brands.

Imagine you are selling a product, and both the processes of offering and purchasing run smoothly, completely satisfying the customer. Theoretically, the you have won the client’s trust. In practice, however, this trust can always be shaken at some point due to some limitation of the product or even by actions of a third party. This makes the whole process of branding, marketing and communication rather more challenging for anyone whose mission is to turn consumers into customers or even brand advocates.

It is interesting to note that the alchemy of trust is complex, delicate and full of variations.

To trust means to have confidence, a word derived from Latin meaning “with faith,” revealing its most comprehensive signification. Indeed, in order to trust or have confidence in anything, we must have the expectation that this thing will cause us no harm or damage. This expectation has two possible sources: reason –which arises when we have data and facts that lead us to believe in something or someone – and emotion, which is the feeling that arises when we want to believe that something will be good for us.

But expectation is only one side of trust; the other is experience. If the experience is good, the relationship will leave a pleasant aftertaste and we’ll want more of it. On the other hand, if it is bad, it can become acidic, sour or totally unbearable. Although everything seems to indicate that experience has rational, evidence-based, fact-driven sources, it must be kept in mind that experience also involves perceptions and sensations that are spawned within ourselves – and are, by definition, subjective. And then we are once again faced with the imponderable.

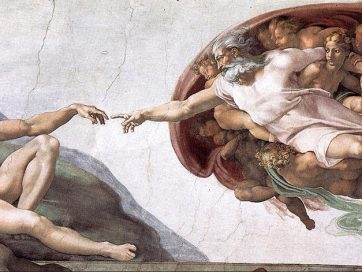

Because of the complex mix of reason and emotion, facts and perception, expectation and experience, trust is to a relationship much as water is to the human body: it represents 70% of the whole and drives all systems, ensures health and the proper functioning of everything.

This can be made clearer with an example: a friend told me that for almost 10 years she had a washing machine of a certain brand, which was not the market leader. When she went to buy a new one, she did not even look at other brands because she already trusted the one she had. But then, two weeks after installing her new acquisition, she began noticing a leak in the laundry room. She immediately suspected the washer and called customer service. She was scared stiff that she had made a wrong choice at the time of purchase. When the technician came, he said the appliance was working perfectly and that the source of the leak was the faucet to which it had been connected. My friend told me that, even knowing that repairing the leak would end up being more expensive, she was relieved to know that it was not the washing machine’s fault. After all, this proved that she had indeed placed her trust in the right brand, that the brand had not disappointed her.

When I hear a story like this I cannot help but think how trust is liquid and sensitive to external factors – it’s like the tides that change according to the phases of the Moon. A ten-year relationship with the washing machine brand had made her trust it, but even a slight suspicion made her insecure. That’s why she was so happy to learn the washing machine had not betrayed her. As the washer was still under warranty, calling the plumber to fix the faucet cost her a lot more. Even so, she was glad to have trusted the right brand. The truth is that consumers feel happier when they have their trust reciprocated – a kind of dynamics that is more emotional than rational.

This incident clearly shows how every relationship is based on the principle of exchange – of giving and receiving. You buy a product and expect to have your expectations fulfilled. This seems simple enough, although it becomes much more complex when it comes to services.

In any activity of the service sector there is a variable that is very difficult to control: the empathy between the company representative and the customer. A wrong tone or a careless reaction can make consumer confidence evaporate. Some years ago, even before the social networks, a certain brand of Brazilian jeans ended up being disliked by many female customers because of the attitudes of the saleswomen at its oldest and most popular store. The news spread by word of mouth, and people started commenting to each other that they would never again go into that again because of the arrogance of the sales team. The jeans were excellent, manufactured with high-grade denim, the cutting was flawless, the communication was excellent, the ads were in every magazine and the brand was always part of the fashion weeks. But bad customer service ruined everything. Customers no longer trusted they would be treated well in the stores and began purchasing other brands. And here is yet another aspect of trust: the brand owners had trusted the wrong people or were so overly confident in the product’s quality that they did not realize what was happening. It is also possible that they did not have anyone trustworthy tell them clearly which was the broken link of their strategy. Today the brand is no longer on the market.

That is why companies invest so much in winning the consumers’ trust. The problem is that many of them invested wrong over the last century. They talked more than they walked. They told excellent stories in their commercial films, but they did not make history. The strategy of doing more storytelling than storydoing backfired. The result is that today’s consumers are becoming increasingly suspicious.

This feeling of mistrust creates a very difficult paradox for marketers: the more successful a business, the more visible and vulnerable it becomes to “haters”.

These “haters” believe that the more money a company invests in advertising, the less trustworthy it is. Depending on how consumers feel about a brand, they will tend to interpret any intense advertising campaign as an brainwashing attempt. So, the all the investments in the brand not only will not have the desired effect, but will also end up fomenting mistrust – or, even worse, will mess up the expectations of loyal consumers, who suffer the most when the brands they once trusted disappoint them.

A certain bank launched an advertising campaign stating that it supports entrepreneurship. It is bound to strongly disappoint clients who visit a branch after financial support and might get a cold or even disdainful treatment from the manager. The bank’s ads and films create an expectation and if reality does not match it, disappointment will be so great that it turns into grief, it becomes personal offense. Before the Internet, this kind of disappointment was restricted to the personal circle of customers; today, it ends up in the social networks and gains enough volume and reach to cause considerable damage to the image of an advertiser who decided to sugarcoat reality.

That’s why it’s so important to have good, proper, common sense. Advertising is still the best way to reach people. However, as the critical judgment of consumers is increasingly sharp, campaigns need to find the right tone and announce what the company actually delivers. This creates trust among people at large and also among the company’s employees. Recently another bank ran a campaign saying it was calling customers to offer credit alternatives to keep them from getting deeper into debt. Account holders who received a phone call from their manager mention this to their family and friends and this helps to increase confidence in the bank’s work. The bank’s employees, who know that this policy is for real, feel likewise more valued and confident. In other words, if you tell the truth, you can be confident on the return on your advertising dollars.

Speaking and acting according to the truth makes you trustworthy. It’s as simple as that.

This is a matter of strategy and is one of the topics discussed in the book SEM: Sistema de Estratégia Minimalista (MSS: Minimalist Strategy System), particularly when we talk about the 4 Es that should guide the management, marketing and communication processes.

The 4Es and trust

By applying the 4 Es – Elegance, Efficiency, Eloquence, Eminence – to a company one generates trust both externally (in the final product) and internally (in its operational processes) – and, of course, in the relationships between the people who build the company as well.

When principles related to Elegance are applied – particularly the premise of putting the customer’s interests and comfort at the center of every initiative – all professionals tend to feel more self-assured about their role in the company and confident to the point of seeking to improve deliveries. Which brings us to Efficiency.

The concept of trust is closely linked to both building more efficient processes and delivering results to the end customer. Companies that work in a climate of internal trust are more agile, more synergistic. The different departments do their work knowing that it will be honored and valued by the next step of the production chain. For example, in a restaurant, the maitre d’ must trust that the cook will prepare the dish according to the customer’s request, the chef must trust that the buyer brought the best ingredients, and so on. Each specialist needs to trust the professional with whom he or she interfaces. The result will be a better delivery to the end customer, which also tends to optimize financial results.

Trust is also the basis of Eloquence. A trustworthy product, service or operation speaks for itself; it does not need millions invested in make-believe. And there’s one more aspect: when people trust a product, they become its advocate and the brand gets the best kind of advertising there is: word-of-mouth, often full of enthusiasm and credibility.

To conclude, the presence of Trust in the entire production process inevitaly materializes in Eminence – that is, success.

Therefore, whenever something truly subverts a company’s image, the immaterial losses are as great as the eventual losses in sales or market share.

The meat is weak

Recently, Operation Carne Fraca [weak meat] made it clear that in today’s globalized economy, a crisis of confidence can have planetary repercussions. This crisis in particular showed that a breach of trust can sause immense and immediate financial losses.

One of the companies that suffered the greatest damage with the disclosure of a list of people involved in corruption was JBS, owner of the Friboi brand, featured in a series of multimillion-dollar advertising campaigns in recent years. Although the indictments of Brazil’s Federal Police did not relate to the quality of the products, the public did not forgive the company. In a matter of hours, a wave of jokes and memes with the stars of campaigns began circulating on the Internet. The crisis of confidence caused by the possible actions of an executive in one of the company’s units not only tarnished the Friboi brand but also damaged the credibility of the stars who were the celebrity endorsers of the brand, like actor Toni Ramos and singer Roberto Carlos , whose respective auras of credibility were shaken by the negative contamination caused by their proximity to the brand.

The fact is that, much like humans, companies also make mistakes. In such cases, the most important thing is to recognize one’s errors, be transparent and quickly right the wrongs. This is quite helpful in regaining consumer confidence.

There is no denying the impact that the news can have on people’s confidence in brands, personalities, and institutions. That is why it’s so important for the public to assess carefully which sources can be trusted. In this regard, an issue that is being recurringly debated involves the credibility of non-mainstream news sources, especially bloggers and social media pages. Most worrisome is the fact that news posted on site and social networks can be subject to artificial viralization, that is, the news doesn’t get millions of shares naturally, but through robots that dodge the defenses of search engines and social networks and use their algorithms as a distribution platform.

A recent article in Forbes magazine showed that, combined with big data on the habits and preferences of millions of people , the use of an artificial intelligence software caused anti-Hillary and pro-Trump news to reach more efficiently those most inclined to agree with Trump’s political platform. The entire process of generating news, often distorted or false, combined with delivery aimed at an audience clearly inclined to believe and share this news, is a way to manipulate the communication process using the trust people have in the opinion of friends as a political weapon.

Trust and synergy

The dynamics of expectation and experience that form the alchemy of trust apply particularly to the relationship between companies. Co-branding and co-marketing actions are based on one company trusting the work performed by the other, as expressed by the history of each one and by the relationship among the professionals charged with interfacing between the companies. Yes, it is subjective. But trust, as mentioned, has an important personal component.

The possibility of trusting the work and competence of other people is also the basis for synergy, a fundamental force for the development of companies. Without trust, it’s impossible to work together and that is why it’s so important that company leaders foster a climate of trust and cooperation within their organizations.

There is a clear relationship between trust, cost reduction, increased productivity and the generation of wealth. It is the logic of running tabs or selling on the cuff – i.e., on informal credit or on trust. Although it might seem like the stuff of small-town grocery stores of yesteryears, it is still an option that exists in several places. Selling on the cuff is an operation based on trust. For the seller, the advantage of giving credit to customers is to ensure their loyalty. Over time, one discovers what loyal customers want and like, and that helps in negotiations with suppliers. Sellers know that they’ll have to keep their prices aligned with those of the market so as not to betray the trust of customers, but the constancy of sales is an important advantage. Today, selling on the cuff has other advantages: it eliminates the cost of money both for the seller and for the consumer. The seller is freed from credit or debit cards charges and the customer is freed from interest charges. This only goes to show how trust is worth its weight in gold.

After all, whether in family, love, professional, commercial, business or institutional relationships, trust is the foundation of everything.